Exploring the Cost of Capital for SaaS Companies – Series Intro and Part I

[ad_1]

This series of blog posts focuses on the equity cost of capital (sometimes called cost of equity, required return, or Ke) for private Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) companies. But what the heck does that mean, and why is it of interest?

If your business needs money, you can “buy” that money by issuing debt (notes or bonds) or equity (stock or shares) – and buying that money comes at a cost. For debt, the price tag is usually written down up front: you pay an interest rate, possibly with some other fees or costs, but the overall cost is generally easy to determine in advance.

However, the cost of equity has always been shrouded in mystery and uncertainty. Instead of a known interest rate, equity pricing is done by selling a percentage of the company. What exactly that costs you can’t be known until some future moment when the company eventually exits. If you had a crystal ball about the future, you could estimate the cost accurately (but you’d probably just take that crystal to Wall Street and make a killing, instead).

This uncertainty has traditionally been great for equity investors. They obscure the price tag, and “sell” their money as prestigious, value-added, and paired with helpful advice. (That can all be true, too, by the way – I spent ten years truthfully selling money to entrepreneurs that way.) But it’s not great for entrepreneurs, who deserve a more transparent way to compare their financing options.

Particularly today (2023) when valuations are low and equity costs are high, it’s important for SaaS companies to figure out their cost of equity. There are many angles on this topic, so we don’t propose a single “silver bullet” – but in this blog series, we take different lenses to the topic, which together make a strong case for a range of equity cost estimates supported by the data. In this first part of the series, we look at public market comparables.

Part I. Public Comps, and the Cost = Return identity

Underlying the use of historical data is this fact: the cost of equity must ultimately be the same as the returns to equity. (This may be the most important fact in this series: the cost of equity is only known after the fact, once the returns become known.)

Therefore, one way to approach estimating the SaaS cost of equity is to analyze historical data. If we can determine the historical returns to equity, we know the historical cost of equity (even if the parties involved didn’t know it at the time).

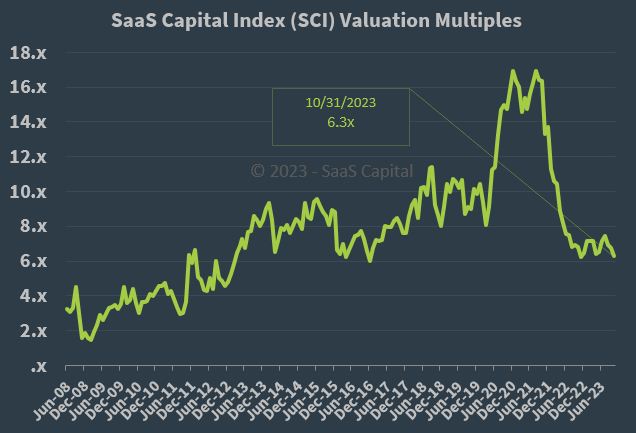

Because SaaS Capital has been maintaining the SaaS Capital Index (SCI) for over 10 years, we have a uniquely useful dataset on historical equity returns for SaaS companies. We took all 14 of the 10+ year SCI companies that were still public as of August 2023 and examined actual realized returns (not just stock price changes, but including splits, dividends, etc.). We call this group the “LTSCI” for Long-Term SCI.

10-Year Results

We looked at the 10-year returns first, which is a pretty good starting place for the definition of “long-term.” (For example, the 10-year treasury yield is often used as a baseline for long-term stock returns.) Overall, the LTSCI posted a total return of 22.1% annualized over the 10-year period.

In contrast, if you had bought the 10-year treasury in August 2013, you’d have made 2.7%, and if you bought the S&P 500 index, you’d have made 12.5%. Buying SaaS company stock was a fabulous investment in 2013 – but selling SaaS company stock was exorbitantly expensive at the time, with a realized return (and hence, cost of equity) of 22%.

5-Year Regimes

What we found inside the 10-year performance is that there were really two regimes, the first and second five years.

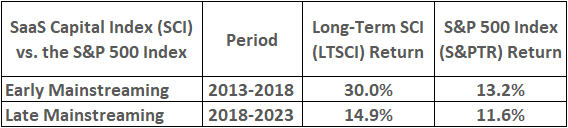

As you can see, the broad stock market (S&P 500 Total Return) was relatively similar in both regimes. But during the Early Mainstreaming period of 2013-2018, SaaS companies hugely outperformed, before becoming more like other large, mature industries during the Late Mainstreaming period of 2018-2023.

In 2013 at the beginning of Early Mainstreaming, SaaS was an established concept in technology, but the wider business world was just catching up to its potential. And, not to overstate our own importance, SaaS Capital had only just been established (circa 2012). Investors were under-allocated to SaaS in 2013, leaving valuations relatively low and prospective returns high.

Conversely, by the Late Mainstreaming period in 2018, SaaS was the new de facto standard business model for B2B software. SaaS investment was in the mainstream and valuations were fulsome, with the previously-available arbitrage traded away by investors who were now familiar with SaaS.

Whether we are now in a stable regime is a very fair question given the frankly crazy conditions that prevailed during the COVID response period of 2020-2021. We believe that even considering that craziness, the period of 2018-2023 taken as a whole fairly represents a stable regime for SaaS company financing. To see why, consider the chart of the SaaS Capital Index below:

As you can see, the results from 2022-2023 have “reset” SaaS valuations back to a level that essentially ignores the 2020 bubble. The return has, nevertheless, been healthy since 2018, taken overall and spread over the five-year period, and we think it represents the increase in the fundamental value of public SaaS companies in that time – primarily driven by the actual growth of revenues. (We will return to this topic – of fundamental growth – in a later part of this series.)

Our conclusion is this: public comparables support a cost of equity of 14.9% when applied to mature public companies of scale over $100 million.

Next, in Part II: We will explore how to adjust the public company data for smaller, private SaaS company cost of capital.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link