ACV (Annual Contract Value) vs ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue)

[ad_1]

After commenting on a post by SaaSMetrics, I realized how much confusion and mixed definitions there are on the difference between ACV (Annual Contract Value) and ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue), which prompted me to think — “I need to research this a bit more”. I want to breakdown my explanation and findings, and define where confusion currently exists.

First let me start by saying ACV tracking and calculation is never really unanimously agreed upon, even by major SaaS businesses who do seem to know what they’re doing and how they are onboarding customers. This causes some pretty serious confusion. However you calculate it, whether how I suggest, or in your own way, that your company is all on the same page with how you are measuring ACV. I will answer your questions and give you examples as to why you, and all of us, are probably confused.

Annual Contract Value (ACV) Definition

Annual contract value (ACV) is an average annual contract value of your account subscription agreements. For companies that also charge one-time fees in conjunction with recurring fees, the first-year ACV might be higher than later-year ACVs in a multi-year contract. This is how I would define it at least.

Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) Definition

Annual recurring revenue (ARR) is much less confusing and is typically agreed upon. I will grab the definition from Zuora for us. ARR is the value of recurring revenue of a business’s term subscriptions normalized to a single calendar year. What does that look like on paper? Let’s say Jack purchases a four-year business service subscription from Jill for $20,000. If we normalize the full-term revenue to a single year, our ARR would be $5,000 because that is the yearly income on that subscription.

ACV vs ARR Customer Example

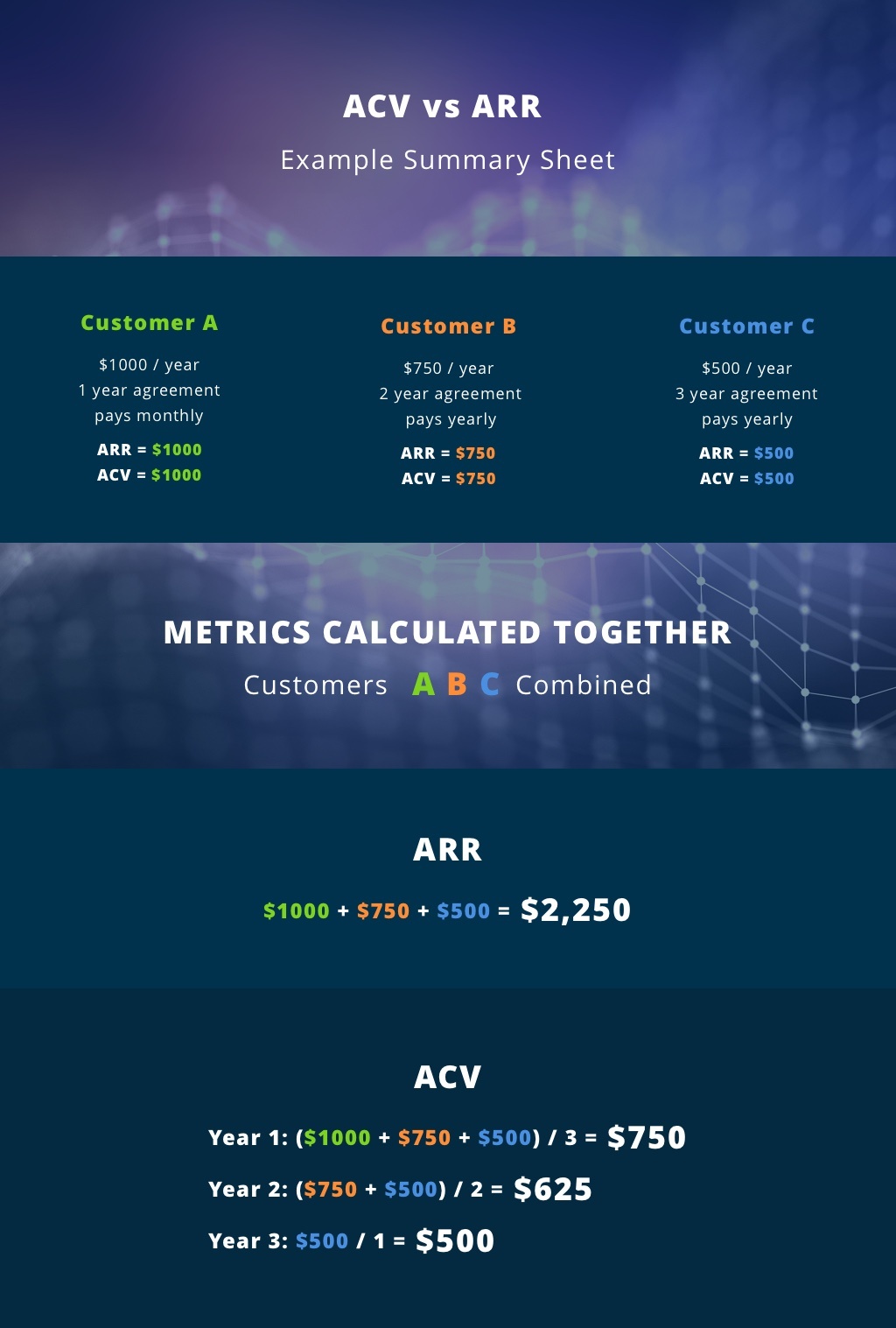

Here is an example of ACV vs ARR calculated with 3 example customers, which we will use to explain the differences of both:

Customer A

Customer A agrees to a $1000 / year, 1 year agreement, and pays monthly.

Metrics calculated for Customer A Only:

Customer B

Customer B agrees to a $750 / year, 2 year agreement, and pays yearly.

Metrics calculated for Customer B Only:

Customer C

Customer C agrees to a $500 / year, 3 year agreement, and pays yearly.

Metrics calculated for Customer C Only:

——————–

Metrics calculated with all three customers A, B & C combined:

- ARR = $2,250

- ACV =

- Year 1 = $750

- Year 2 = $625

- Year 3 = $500

——————–

Here are the calculations broken down:

- ARR: $1000 + $750 + $500 = $2,250

- ACV:

- Year 1: $1000 + $750 + $500 / 3 = $750

- Year 2: $750 + $500 / 2 = $625

- Year 3: $500 / 1 = $500

What Does This Mean?

So as we can see from my definition, ACV is how much, ON AVERAGE, your annual value of a given contract type across all customers of the period is worth. This is the primary difference between ACV and ARR. If you were to add the contract values to calculate ACV then it would come out to the same outcome ($2,250) as ARR just with a different way of getting there.

Let’s take HubSpot’s ACV as an example, it is around $6,000 – $10,000 (just a guess based on this Quora post). It would be much higher if you were to add all of the signed committed agreements for the year, let’s say 1000 contracts x $10,000 = $10M, quite a difference.

ACV Bookings

ACV Bookings however, refers to the total value of accepted term contracts. This means you would add them together vs average them. ACV Bookings are only calculated for 1 year vs multi-year. For beyond one year, TCV (Total Contract Value) comes into play.

TCV (Total Contract Value)

TCV (Total Contract Value) is calculated to see total values of multi-year contracts (this could be yearly contracts or subscriptions that have a termination period, but ongoing subscriptions with no defined end are not included). In our previous example here is how TCV would breakdown:

- Customer A TCV = $1,000

- Customer B TCV = $1,500

- Customer C TCV = $1,500

TCV of Customer A,B and C combined = $4,000

Adding in Implementation Fees, Onboarding Fees, Training, etc.

There are quite a few ways to spin this and it depends on how you package your agreements, how granular you want to get, and ultimately what works best for your business. In my opinion, to simplify, I would associate all fees within a contract as part of the final agreement, given they are a part of the agreement. In the examples above you could simply have calculated one-time fees, onboarding fees, and training included within the numbers for the same outcome.

For example:

- Customer A agrees to a $1000 / year, 1 year agreement and pays monthly, which includes onboarding fees.

- Customer B agrees to a $750 / year, 2 year agreement and pays yearly, which includes an implementation fee and training fee.

- Customer C agrees to a $500 / year, 3 year agreement and pays yearly, which includes onboarding fees and implementation fees.

At the end of the day this would give you a healthy understanding of your ACV and if you wanted to you could always dig in deeper and get more granular by separating calculations later. Alternatively, some people find it easier to visualize these things often using Gantt charts to help them.

ACV Calculated with Expansion Revenue & Churn

To truly calculate ACV more accurately you would want to include Expansion Revenue and Churn.

ACV = New Customers + Expansion or Existing Customers – Churned Customers.

There is a great breakdown of this on For Entrepreneurs where you can read more about this.

Why ACV Might Confuse You

Here are the reasons for your confusion. I may be wrong, but I have researched this a lot and trust me there is confusion everywhere within this subject, but these are my conclusions.

1. ACV vs ACV Bookings – ACV alone is used as an average to understand the average value of your contracts. This is why I look at the following years also. Where as ACV bookings is generally used as a total of your contracts for a 1 year period. When using ACV bookings for a 1 year period you will also see TCV bookings calculated to total multi-year contracts. Sometimes ACV and ACV Bookings are used interchangeably, which in my opinion they should not as they are two separate calculations.

2. Most of the time when calculating ACV people only give an example for 1 customer, which then leads the person to wonder, do I add my customers together or average them to get my calculation?

3. If I would have stated that the agreements were not per year, and instead:

- Customer A was a $1000 agreement for 1 year

- Customer B was a $750 (total, not yearly) agreement for 2 years

- Customer C was $500 (total, not yearly) agreement for 3 years

Then the calculations would calculate differently like this:

Year 1:

- Customer A: $1000 / 1 year = $1000

- Customer B: $750 / 2 years = $375

- Customer C: $500 / 3 years = $166.67

Divide by 3 to average them.

$1000 + $375 + $166.67 / 3

Year 1 ACV = $513.89

——————–

Year 2:

- Customer A: Not Included

- Customer B: $750 / 2 years = $375

- Customer C: $500 / 3 years = $166.67

Divide by 2 to average them.

$375 + $166.67 / 2

Year 2 ACV = $270.84

——————–

Year 3:

- Customer A: Not Included

- Customer B: Not Included

- Customer C: $500 / 3 years = $166.67

Divide by 1 to average.

$166.67 / 1

Year 3 ACV = $166.67

ACV Confusion Identified and Explained

Here are reference examples of the confusion.

Scenario 1 – SaaSMetrics.co

ACV measures the value of the contract over a 12-month period. So let’s say a customer commits to a 24-month contract of $120,000. Considering this money will be recognized as revenue ratably, we’ll have $5,000 in MRR and therefore $60,000 as your ACV.

It is clear for one contract but this does not specify the outcome of more than one contract so I am not sure if I add or average.

Scenario 2 – Pipetop.com

Annual contract value (ACV) is an average annual contract value of your account subscription agreements.

This is my definition as well.

Scenario 3 – Zuora.com

Annual contract value (ACV) typically maps to an annualized bookings number. For companies that also charge one-time fees in conjunction with recurring fees, the first-year ACV might be higher than later-year ACVs in a multi-year contract.

This uses the term annualized bookings and average is not mentioned at all. This leans towards the idea of adding all contracts together vs finding the average value.

Scenario 4 – Venture Sandbox

ACV Bookings vs TCV Bookings: ACV (Annual Contract Value) counts the expected revenue within the first year, even though some contracts may be multi-year. In order to account for those multi-year contracts we have the TCV (Total Contract Value) metric. We look at both, but care primarily about ACV Bookings.

This uses the term bookings but then does not use the term bookings within the definition. It also doesn’t specify how to calculate ACV (or ACV Bookings) with more than one customer. It leaves you asking, should I add or average?

Scenario 5 – SaaS Optics

SaaS Bookings – Broadly speaking, bookings refers to the total value of accepted term contracts, contracted work or services, and changes to such contracts as of either the order date or the effective date of the transaction.

This simply is used to back up the fact that bookings is used to define total value and not average value. So when adding Bookings to ACV Bookings it would be a total value of first year vs average. Even more confusing is how sometimes bookings may not total multiple years but count them as renewals instead. Either-way though this would total first year value of contracts.

In Conclusion (Phew…)

I didn’t go into this planning on breaking this down quite so much, but as I dug further I found so many discrepancies that I started second guessing things and breaking this down for myself as well.

If you get anything out of this, I hope you have a clear way to calculate ACV and ARR for your company. And most importantly it should be defined so to be consistent with they way the rest of your team agrees to calculate and measure it.

Originally published March 3, 2017, Last Updated March 8 , 2020

[ad_2]

Source link