Changing ACVs: The Hidden Control Lever of SaaS Company Value

[ad_1]

ACV, or (Annual) Average Contract Value, is a SaaS company’s usual price tag: the amount each customer pays, on average. Although some SaaS companies have widely diverse customer profiles, most early-stage SaaS companies (under $100 M in revenue) tend to lock in on a typical deal size.

There are lots of reasons for variation in ACV, including vertical (selling to hospitals is different from selling to law offices, for example), go-to-market approach (Product-Led Growth, or “PLG,” has lower ACV than “bag-carrying salesperson” growth), etc. And that’s OK; it’s far more important to find a great product-market fit, and a repeatable sales motion, than it is to try and optimize for the highest contract value, all else being equal.

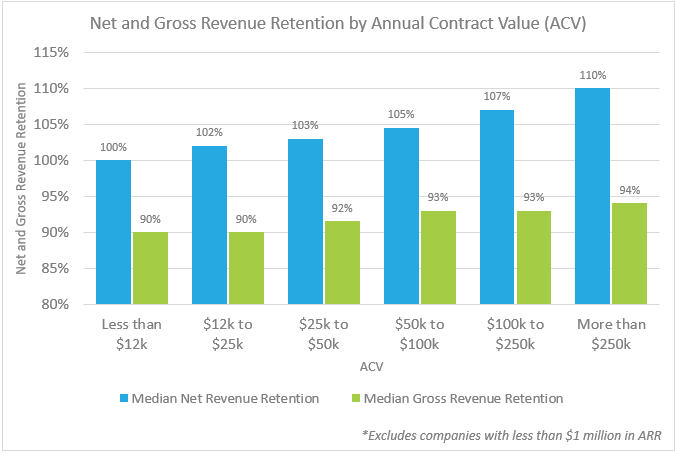

That said, ACV isn’t equal, and the size and rate of change of your ACV does matter: our SaaS Capital Annual Benchmarking Survey results consistently show that higher-ACV companies tend to have better metrics, particularly around retention, as shown in the graph below:

But ACV isn’t – and shouldn’t be – a static quantity. It’s often given at a point in time: the ACV as of today, unlike rates of change like, say, ARR Growth Rate, or Net Revenue Retention. It’s therefore seen like an inherent fact, a sort of “output” of the business, rather than as one of the inputs or levers that management can control.

We think ACV is far more important, and far more in an operator’s control than is usually considered so. We have both qualitative and quantitative reasons for this belief, and we hope the rest of this blog post will convince you as well.

ACV Change Over Time Is Largely In Your Control

There are three ways to grow ACV:

Changing how you price and sell, a.k.a. “go to market” (for example, targeting a larger-sized customer profile) is entirely within your control, though not without tradeoffs (for example, a longer sales cycle). Requiring customers to renew at higher price points, similarly, will be a tradeoff with retention (although if you are providing enough value, retention may stay stable), but also definitely in your control.

Growing ACV by selling more to existing customers might be by means of “up-sell / cross-sell,” which can be influenced, if not entirely controlled, by your account management practices. Or, it may fall into “Usage-Based Pricing,” which we estimate is now used by almost a third of the borrowers we evaluate (and growing). While Usage-Based Pricing can make ACV climb automatically when customers use your software actively, there may be risk to gross margins and revenue predictability if the usage is tied to a commodity (like gigabytes, minutes, or payment flows) which might be subject to volatility in costs or in sustainable market pricing. Also, we are generally not proponents of penalizing your customers for using more of your product. You want to think carefully about cost for value received and ensuring mutual alignment (“win-win”).

When and Why Should You Change (Grow) Your ACV?

We examined an internal dataset from our borrower portfolio, where we anonymized certain data about the change in ACV year-over-year, the absolute level of ACV, and measures of growth and retention. Here’s what the data says about changing ACV:

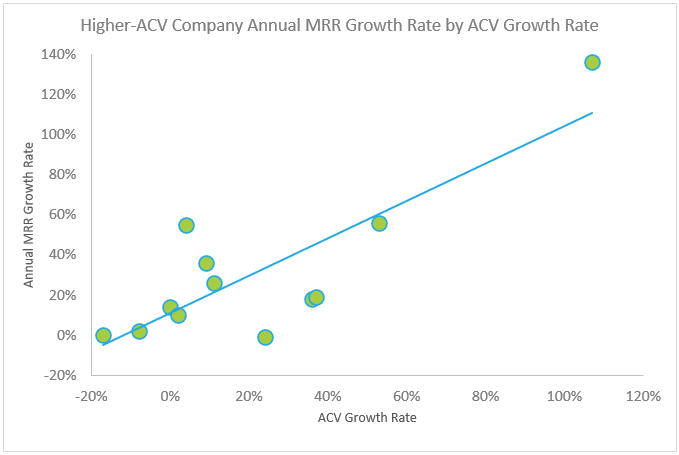

For #1 above, let’s look at a graph including a linear regression from that analysis:

As you can see, although most companies here have modest (0-20%) ACV growth, those with higher ACV growth tend to grow faster, and those with flat to shrinking ACVs grow the least.

This makes intuitive sense, for the same reason that Net Revenue Retention is so highly correlated with growth: in fact, they’re closely related concepts.

The big difference is that you can only increase Net Revenue Retention by keeping and upselling your existing customers, while you can also change your ACV by targeting new customers who yield higher ACVs.

NRR, therefore, is always going to be anchored to how things were a year ago or more, while a change in ACV can result from the new customer profiles, and new pricing strategies, you pursue during the year.

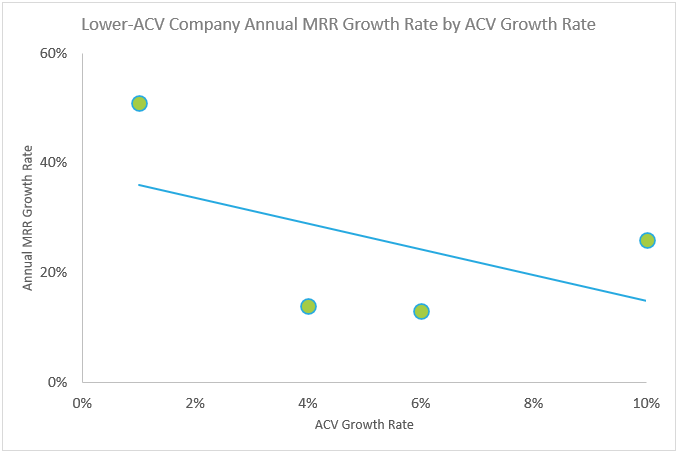

What Should Low-ACV SaaS Companies Do?

It’s not necessarily clear from the data that lower-ACV B2B SaaS companies – who might have annual per-customer billings of $25k, $5k, or even less – should pursue higher ACV strategies automatically. It might be well-suited to a very short sales cycle (such as the elusive PLG path) to have a low barrier to entry, and with a high onboarding rate, the averages might never work out to show a meaningful growth in ACV, despite a healthy growth in revenue. That’s probably OK.

That said, we acknowledge we have less data about low-ACV companies, in part because we lend to fewer such companies. That, in turn, is because the financial metrics of mid- to high-ACV B2B SaaS business tend to be more compelling for our model. It might be right for you, however, to continue pursuing a low-barrier go-to-market strategy, such as product-led growth.

Should You Ever Reduce Your ACV?

We have seen time and time again that it is far more beneficial to go up-market than down-market. Companies that offer low-ACV, self-service products can build more modules and features and hire sales teams and then sell higher-value, higher-ACV configurations. It is much harder for an enterprise SaaS company to “de-tune” the product, which is probably fairly complex, and requires a consultative sale, significant training, and onboarding, to be successfully self-service. The vision of a vast market of self-service customers (or PLG) waiting to sign up en masse is often a mirage.

More generally, cutting prices is a bad sign in B2B SaaS. The path to success generally involves becoming more valuable and “stickier” to your customers, by building deeper and wider capabilities. If you are cutting your average selling price, that’s a strong yellow flag that something isn’t working.

Don’t mistake this observation as ruling out a true “pivot” – sometimes, you may need to sell something completely different, or completely differently, in order to change directions. But managing an existing SaaS business by reducing the average contract value is entering a “danger zone.”

Lastly, as we know, ACV and retention are closely linked. We have heard companies argue “the growth from the PLG product will more than offset the increase in churn”. That is a dangerous gamble, and one we’ve seen lost more than won.

What Does ACV Show About How Customers See Your Company?

Because the customer is willing to pay you this amount, your ACV is the floor on the amount of value you’re providing on average. You provide more value than this, of course, which is why they pay it willingly – the extra value is the “consumer surplus.”

Continuing to walk ACV upward (until you get resistance) is a smart way to ensure that you are capturing as much of the surplus as the market will bear, in economic terms.

But in behavioral terms, it might be good to think about rising ACVs as holding your business to a high standard: your customers (old and new) will only continually increase what they pay if you, in turn, increase the value you deliver. By demanding higher pricing of your customers, you are asking them to demand higher performance of your team, as well. This virtuous cycle of creating mutual value might well be the most important part of the lesson of ACV.

For more peer benchmarking, using real (anonymized) responses from over 1500 SaaS operators, join our SaaS Capital network and participate in our annual survey.

![]()

[ad_2]

Source link